Though I’m surely late to the party, a couple of months back, I stumbled on the book Astroball: The New Way To Win It All by Ben Reiter. The book chronicles the meteoric rise of the Houston Astros organization from one of the worst teams in baseball in the early oughts and their journey to World Series champions in 2017—an outcome predicted & spotlighted on the cover of the June 2014 issue of Sports Illustrated.

As I have watched the San Diego Padres drastically underperform their star-power potential and most fans’ expectations this season, I looked to this book to offer a new perspective of a proven multi-year approach to building a dynasty-caliber team. The interesting context for this book is that it was published before the Astros’ now-infamous sign-stealing scandal was revealed to the public a short while later1.

Trust the Process

To his credit, Reiter did a great job of chronicling the history and approach of the then-Astros General Manager, Jeff Luhnow who moved over from the St Louis Cardinals in 2011. During his time with the Cardinals, Lunhow had established a proven track record of scouting and player development. His philosophy was to invest in the right set of draft picks and minor leaguers, who would eventually produce in the Majors at a fraction of the cost of acquiring big-league talent after they arrived.

Coincidentally, the Padres’ current GM, AJ Preller, has a similar history; a start in the scouting department for the Texas Rangers in 2004 before a promotion to Assistant GM and finally arriving in San Diego in 2014. Unfortunately, streaks of Prellerpalooza, abandoning the Luhnow method in favor of quick returns via big acquisitions (which tend to blow up the farm system) have been one of the few consistencies about my Padres in recent years.2

The key player to unlock the potential of this plan was Sig Mejdal, a mechanical and aeronautical engineering grad who made the jump from stat-head hobbyist to working for the Cardinals after being inspired by Moneyball (2003). Mejdal had worked to compile a massive database of stats to help rank college players in ways never before done at the time; things like adjusting player performance for their conference strength, ballpark favorability, and more. Mejdal would follow Luhnow and relocate to Houston in early 2012.

The process embraced by Luhnow, Mejdal, and others was not without pain & skeptics; following Luhnow’s arrival, the Astros finished two more seasons with 100+ losses. This made the quick turnaround even more compelling; following a small improvement in 2014 (finishing 70-92), the Astros finished over .500 in 2015 and 2016 before winning 101 games and the World Series in 2017.

Assembling the Right Pieces

Putting aside the sign-stealing scandal for a moment, this book offers a tremendous, up-close view of how a professional baseball organization operates. Everything from the draft to minor league player development, to roster construction, player swing modifications and transactions at the trade deadline; for a long-time baseball fan, this story is essentially a sequel to the Oakland Athletics Moneyball tale by Michael Lewis.

A couple of subplots resonated with me for the way they highlighted the deeper level of dynamics at play within an organization. First, the scouting and drafting of Carlos Correa. Though not a unanimous one-one (first round, first overall) pick, the Astros knew his disposition matched his promise as a young star. But perhaps just as importantly, Correa would sign with Houston for well below the maximum signing bonus for a first-overall pick. The unspent cash could go towards their next pick(s). Additionally, a couple of veteran pieces including Carlos Beltran for one year and $16 million, plus the acquisition of Justin Verlander from the Detroit Tigers with just minutes to spare before the trade deadline.

For me, these instances drove home the point of how a winning culture is very much driven at every level of an organization. Leaders like Beltran were pivotal in wrangling an otherwise young roster of players without much post-season experience. But experience alone doesn’t win championships or even guarantee team chemistry; what is consistently revealed by Reiter is the buy-in across the Astros organization to their selected strategy. Furthermore, sustained success is achieved via incrementality, not massive (Prellerpalooza-style) changes from one season the next.

Aftermath & Accountability

Ultimately, most of the blowback from cheating would come not from MLB, but from fans’ and other players’ reactions to the scandal. The official report by the League commissioner Rob Manfred was, by most accounts, pretty underwhelming. By the time the report was released, little new information was uncovered. No players were punished since they were offered immunity in exchange for their full cooperation. The fines levied against the club were a measly $5 million to an organization worth nearly two billion dollars.3

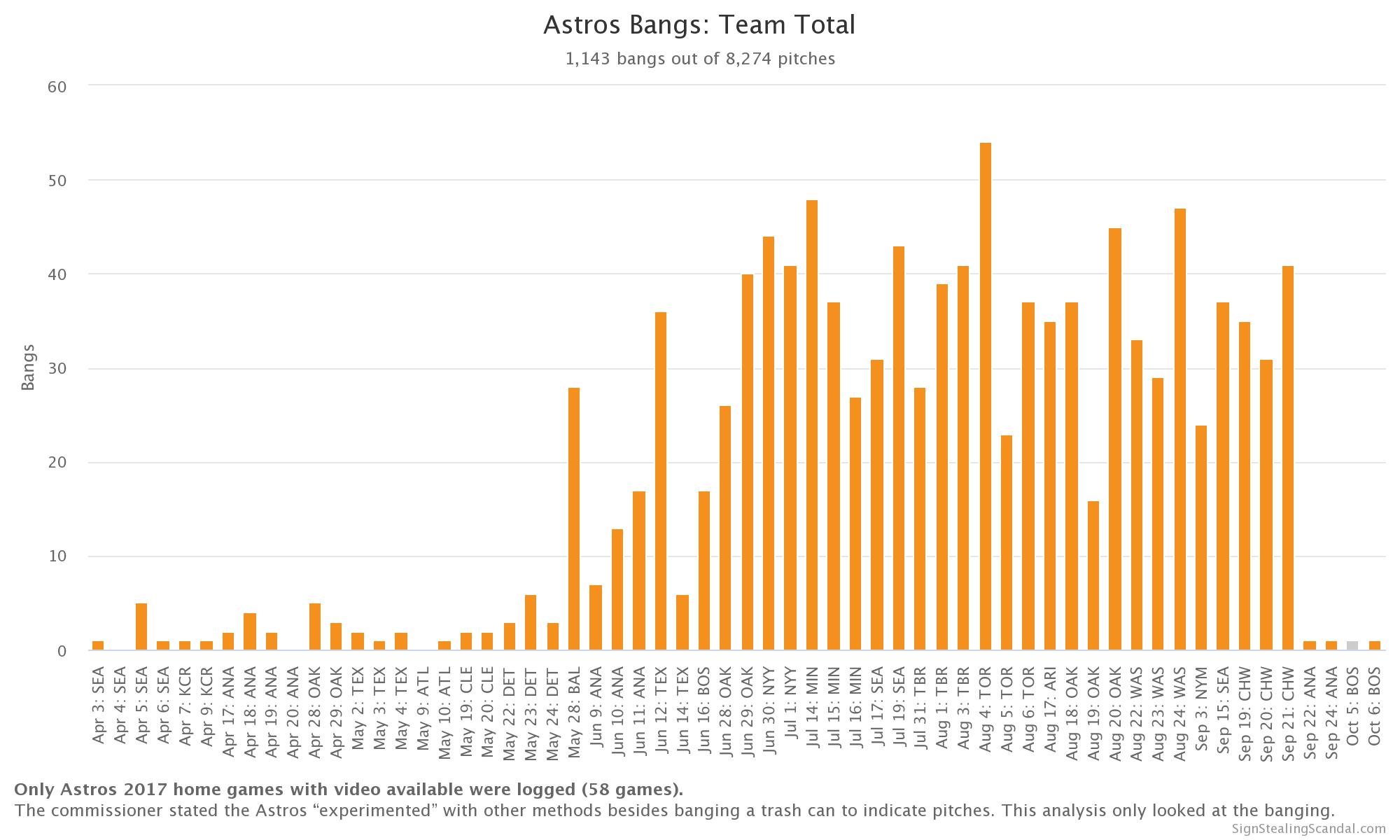

Credit Jomboy,4 Ken Rosenthal and one particularly dedicated Astros fan (who published SignStealingScandal.com) for their reporting and analysis.

The Manfred report did find that most Astros players benefitted from the trash can banging in 2017 and that the scheme was primarily player driven. Multiple reports pointed to Carlos Beltran being the mastermind of the trash can scheme. Oddly the Astros owner, Jim Crane, is explicitly exonerated, while manager AJ Hinch and GM Jeff Luhnow faced suspensions and were immediately fired from Astros. No other cheating that was rumored to have taken place in 2018, including wearing buzzers to communicate signs to batters was substantiated.

Alex Cora, who was the bench coach with the Astros in 2017, stepped down from his then-role as manager of the Boston Red Sox in early 2020, before being rehired 7 months later. Carlos Beltran resigned in disgrace from his new post as manager of the NY Mets before ever coaching a single game.

Culpability & Catharsis

Making sense of a scandal outcome and the suitability of punishment is always challenging. There aren’t comparable examples from which to glean precedent. A natural comparison might be the wave of steroid and banned substance scandals over the prior couple of decades. However, the Mitchell Report, which documented the pervasive nature of illegal substance use in MLB served more as a catalyst to re-architecting the league’s drug testing policy than justification to punish named players.

After strengthening their testing policy, MLB could punish players more swiftly and in a standard way for any violations of the policy, which now requires suspensions as follows:

- First positive test results in an 80-game suspension

- Second positive will suspend players for 162 games (a full season)

- Third positive earns a lifetime suspension from MLB

Comparing those scandals to the Astros cheating is somewhat unfair, though, because testing for banned substances delivers a known result; players either test positive (and therefore broke the rules) or they don’t. Add to this, the fact that players from nearly every team were implicated by the 2007 report. Once the Commissioner’s report was released, Manfred made one thing clear: any further cheating by teams would mean punishing the coaches and managers of the teams caught.

This parallels other bad outcomes resulting from self-governance and conflict of interest in organizations. In cases like Purdue Pharma’s aggressive selling of addictive painkillers, or Boeing’s ignoring employee safety concerns of the 737 MAX and instead prioritizing deadline and budget constraints over safety, you see organizational cultures gradually decay from initially well-meaning in the name of competition to downright unethical or illegal.5

But in the business of sports, organizational misconduct doesn’t typically rise to the level of criminal wrongdoing and doesn’t produce collateral damage as in pharmaceutical drugs and passenger aviation. Maybe a better comparison to draw is that of politics, where a lot of the scandal comes from attempts to cover up bad actions.

And here’s an interesting factoid: though baseball is very much a business (they broke their revenue record in 2022, generating nearly $11 billion), the election of its commissioner operates distinctly from what you might call a democratic process. The threshold for re-electing the commissioner is a simple majority, while the threshold to replace them is three-quarters. On that note, you may not be surprised to know Rob Manfred was recently re-elected to another term as MLB commissioner. After all, MLB is self-governing, with Manfred’s constituents as we’ll call them, a group of 30 billionaires who know all too well6 what it means to run a results-based business.

-

Reiter produced a podcast to serve as a proper epilogue to his book after the sign-stealing story broke. The podcast didn’t offer me much closure or satisfaction, probably just as it didn’t Reiter. Find The Edge: Houston Astros wherever you get your podcasts. ↩︎

-

Since Preller’s arrival in the summer of 2014, the Padres have finished in last or next to last in their division five of eight seasons while making the playoffs in only two, though some refer to this as 1.5 seasons when you consider the 2020 season was shortened due to COVID-19. ↩︎

-

The value of the Houston Astros in 2020, the year the penalties were levied, was $1.9 billion according to Forbes. ↩︎

-

Jomboy’s breakdown of a 2017 game features Chicago White Sox pitcher Danny Farquhar picking up on the scheme while pitching to Evan Gattis. After meeting at the mound with the catcher to mix up the signs, no more bangs were observed in the game, and only two more bangs were observed in the final three games of the season. Jomboy’s later analyses offered me the most cathartic breakdown of the scandal; November 17th Update and Part 2 in February, 2020. ↩︎

-

The bankruptcy case of Purdue in 2021 offered the ownership of Purdue Pharma—the Sackler family—immunity from any future related lawsuits. However, this decision was recently blocked by the US Supreme Court, per CNN. ↩︎

-

This Taylor Swift reference was not intentional, but as her catalog grows, so do inadvertant references. ↩︎